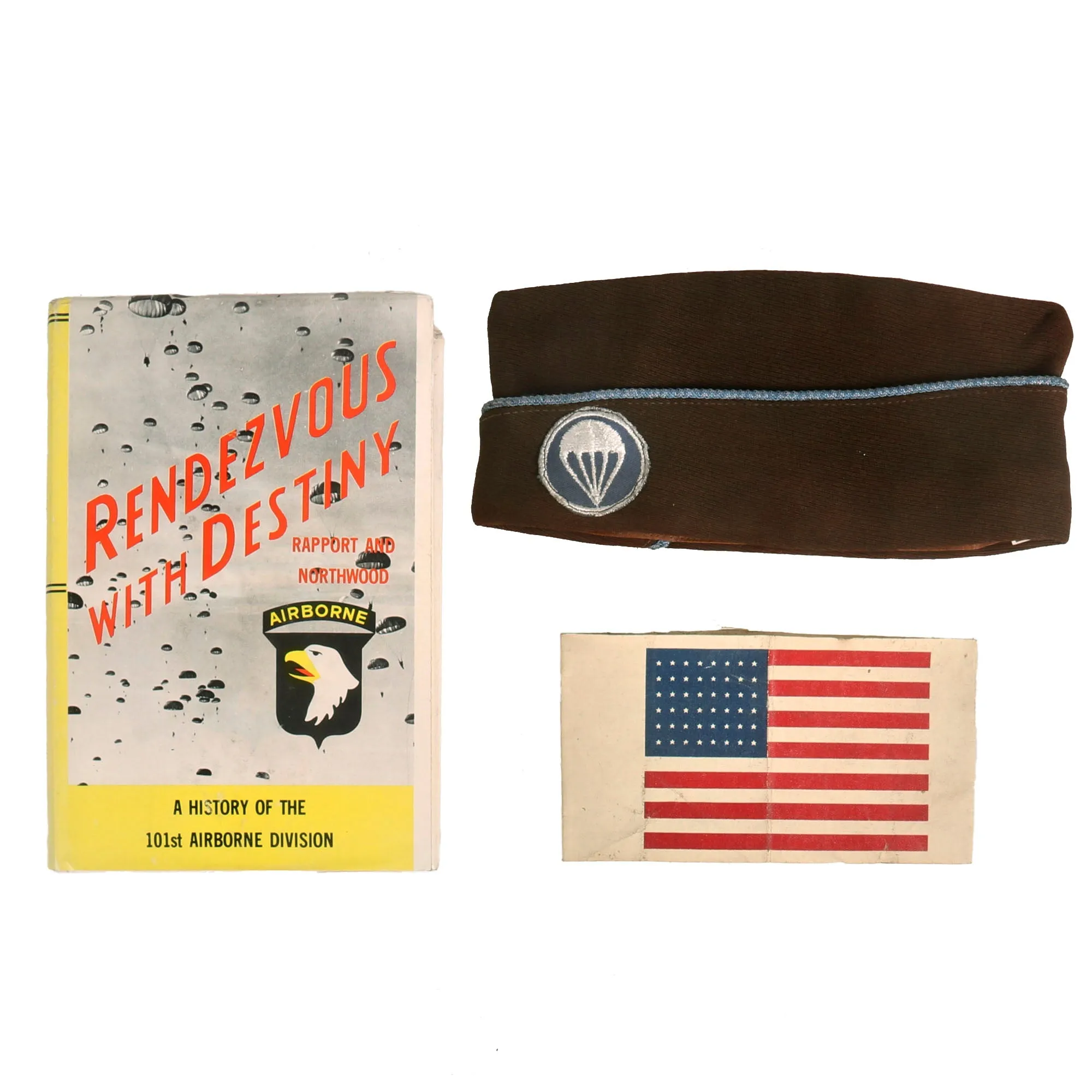

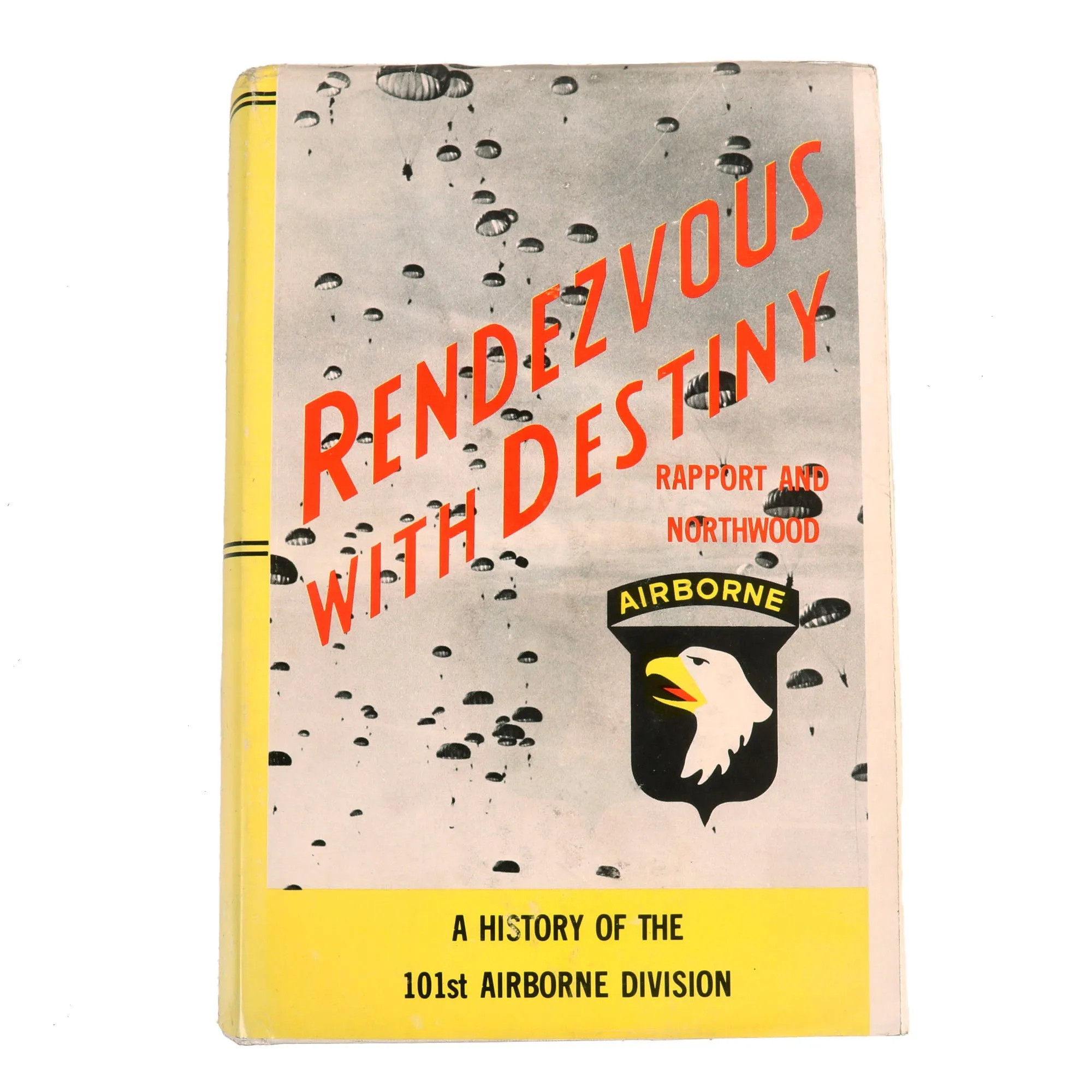

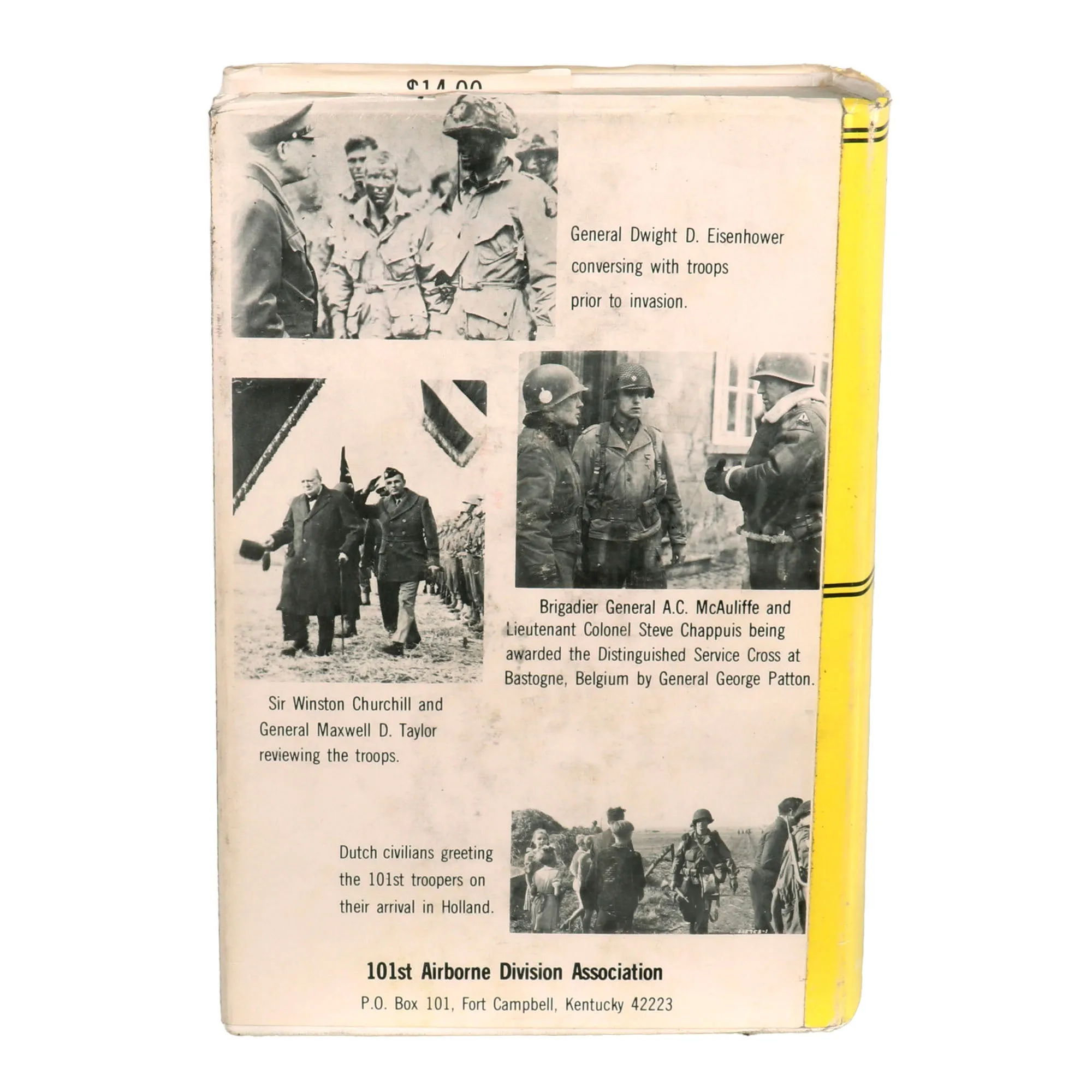

Original Items: Only One Lot Available. This fantastic collection comprises items attributed to George M. Rosie, a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment. The collection includes the book "Rendezvous With Destiny," which has his return address envelope sticker, indicating that all three items belonged to him. The other two items are an Oilcloth American Flag invasion armband with safety pins and a wool overseas cap. All three items are in fantastic condition and would make great additions to any Airborne Division-related collections.

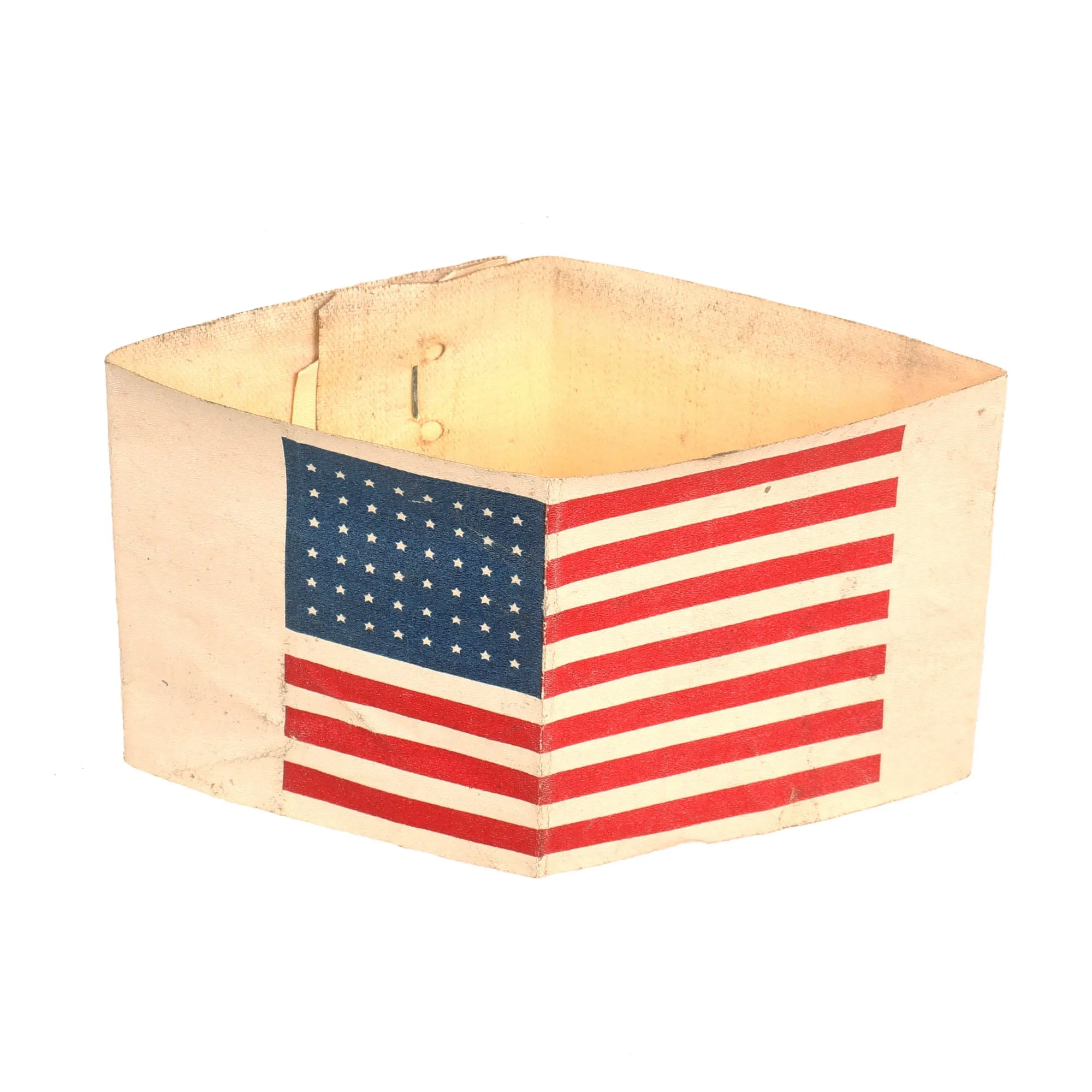

This type of armband was typically used by U.S. Paratroopers, for example in North Africa (1942), during the D-Day invasion in Normandy (June 1944) and during Operation Market Garden (September 1944). The armband was typically fixed to the uniform jacket arm with safety pins.

This is the third type of Arm flag, which was printed as an armband on a kind of sturdy paper stock resembling wallpaper, called oilcloth. This is a semi-waterproof material also called "lacquered cloth" and "American Cloth". It has punch holes and originally came with two safety pins, both of which are present.

Condition is simply extraordinary. This flag shows no signs of ever having been used or attached to a uniform. There is no wear at all to the flag, just some age toning and cracking in the finish. The only difference from when issued is that these were not folded, issued from a stack of flags.

This type was issued for the Southern France, Holland and Rhine jumps and was worn as an armband or cut or folded and pinned to the sleeve. 509th PIR troopers during Operation Dragoon wore their flags on the left sleeve.

There are two variations of this type of armflag, and you will mostly find both described as printed on oilcloth. This is true for the second type, which has a hemmed edge all around, but which is otherwise identical in pattern and size.

The overseas cap is in wonderful, lightly used condition and is offered in size 7. The wool body is in great shape showing no signs of extensive wear or damage. The baby blue piping is correct for WWII Paratrooper use.

A great lot that comes more than ready for further research and display.

An American POW in Germany

By George Rosie, 506 PIR, 101st Airborne Division

Edited by Bill Carrington

Normandy

During mid-May,1944, units involved in the Normandy Invasion started moving toward the marshaling areas near the English coast. George Rosie’s unit, the 3rd Battalion of the 506th, traveled by train to Taunton, Devonshire, in southwest England, then by truck to Exeter Air Base. One of their prior night training jumps had been made from that air base. The area was sealed off and guarded; no one was allowed in or out. They lived in tents and had great food, including ice cream for the first time since arriving in England. They even had movies in the evening.

The mortar platoon studied maps and sand tables of their objectives in Normandy. The paratroopers were issued metal crickets for identification purposes. One squeeze, click clack was answered by click clack, click clack. The cricket was a simple, but effective signaling device. They were also issued ten dollars in French money, 5x3" American flags which were sewn on the right sleeve of their jump jackets, ammunition for folding stock carbines, two hand grenades, and K-Rations. They checked their chutes out and were ready to go. The date was June 4, 1944. The men were fed steak, green peas, mashed potatoes, white bread, and ice cream for their "last supper." As they were enjoying their meal, George remarked to Ronzoni, "They're fattening us up for the kill."

The weather was marked by strong winds causing their departure to be postponed until the following evening. At 8 o'clock the next night (June, 5) they were again down at the planes. By 9:30 some of the planes were starting up, and the men were getting into their chutes and tightening their harnesses. George's thought was, "This is it." With two chutes and full combat equipment, the men boarded the planes at 10:30 p.m. They had so much equipment, they could barely walk and had to be helped up the ladder steps. At 11 o'clock, with 18 parachutists plus their equipment and bundles, the plane took off very slowly. It vibrated and shivered until George thought the rivets would pop out. He looked around at the men. Some were sleeping; some were smoking; some were talking. Others were just sitting there staring straight ahead with blank looks on their faces. George was nervous and a little afraid, but he was so naive and innocent that he had no thoughts of being wounded or killed. Not so with Ronzoni. When they talked about home, with all their friends and family waiting there, he said, "I'll never see home again." Some of the men really felt they were not going to make it and Ronzoni was one of those men.

With a bright moon lighting the sky through broken clouds, they formed a very tight formation and headed for the English coast. The skies were filled with airplanes. Over the channel they could see hundreds of boats starting toward the continent. George had a feeling that they were a part of a big chunk of history. At 1 a.m., June 6, 1944, George heard one of the men yell, "There she is boys." They all knew what "she" was--the coast of France. They were nine minutes to drop zone. Flak and machine gun tracers could be seen to the right and left. George thought, "It looks just like the Fourth of July." A few seconds later, the plane on his right blew up and hit the ground in a large ball of fire. Twenty men were wiped out. This was no Fourth of July celebration. Welcome to the real war.

The red light in the door came on. They stood up and hooked up. Then came the green light and they were out the door; quite a struggle with all their equipment. Someone fell down and had to be helped out. When George jumped, he felt like every tracer in the sky was zeroing in on him. He was sure the rest of the guys felt the same way. He thought their plane must have been flying very low because he could only remember swinging twice before he hit. He could see a man and a woman standing in the front yard of a house just beneath him. He hit the road, took two steps, then went head first through a wooden fence, knocking out two teeth and cutting his lip. He rolled over and tried to get his carbine out. He couldn't, so he sat up and looked around for the man and woman but they had disappeared. He finally managed to get out of his T-5 parachute harness, (those snap harnesses were a bugger to get out of) and pulled his folding stock carbine out. He could hear some soldiers coming down the road. He started up a hedgerow, but felt someone holding him by his belt. He stopped, tried to move again; same thing. He slowly turned around and found that the shroud lines from his parachute were tangled up in the fence. George could hear the sound of hobnailed boots getting closer and closer. He finally got the shroud lines unhooked and climbed to the top of the hedgerow. As he fell over to the other side, forty Germans came marching past where he had been. He could have reached over and touched them. After they passed by, he moved in the direction he thought his plane had come in. George had no experience in his young life that he could relate to being so totally helpless and alone. It was a unique and indescribable feeling.

After a short period of time, he encountered a medic, John Gibson, and one of their 81st mortar men, Charles Lee. It was the greatest feeling in the world, as if he had found a long lost brother. They could hear a German machine gun firing in their area; small arms a little further away. George looked up and could see troopers bailing out of a C-47. The plane was flying in a semi circle at about eight hundred feet The left engine was on fire and flames were streaming alongside the plane near the door. At about six hundred feet it was coming straight at them, troopers and crew still bailing out. The last one bailed out at not more than two hundred feet. The plane went over top of their heads, hit in the enjoining field, and burst into a thousand flaming pieces that lit up the whole area. As four men came running toward them from the direction of the crashed plane, George realized they had been on the same plane he had dropped from: Phil Abbie, Francis Swanson, Leo Krebs, and Ronzoni. The downed C-47 had hit in the area where they were hiding and damn near killed them.

The small army of seven decided to head for the river and find the bridges that were part of their unit's objectives. Hoping to hook up with more of their unit along the way, they stayed close to the ditches and hedgerows for concealment. With Abbie as their scout, the men made their way to a field near the river. Daylight was breaking as Abbie stepped out on the road, with Ronzoni was just behind him. Approximately one hundred Germans were concealed in the field on the other side of the road. Twenty of them stood up, firing their machine pistols. They killed Abbie and Ronzoni. George and Krebs could see a German officer running back and forth on the road in front of them. Krebs said, "What the hell is wrong with that guy? Is he nuts?" Leo and George both shot at him and he went down. A short exchange of gunfire followed, but the remaining American troopers were in a hopeless position. Surrounded by Germans, they were quickly captured. Charles Lee crawled into a wooded area to the left and got away. George was able to get a look Ronzoni and he had been hit in the chest four, five, maybe even six times. He was sure Ronzoni never knew what hit him. After they had been disarmed, George and three other men were lying in a shallow ditch with their hands over their heads, a guard with a rifle on either side. With bullets flying in all directions, Leo Krebs remarked, "God, these guys are lousy shots." Charles Lee began shooting at the guards from his hiding place about fifty yards away. George told Krebs he had a hand grenade in the pocket of his jumpsuit that the Germans had missed, and if Lee could shoot one of the guards, he was going to throw the hand grenade at the other one, giving them a chance to get away. But the Germans circled around Lee and killed him. George left the grenade lying in the ditch. He had lost so much that morning; Ronzoni, Abbie, Lee, his freedom.

After they were taken prisoner, George and Krebs had to pick up the German officer they had killed and carry him back to the farm where the Germans were headquartered. He was the first dead man George had ever touched. When they picked him up to put him on the shelter half, he broke wind and was making strange sounds like he was still breathing. As far as George could tell, they had hit him several times in the chest area and he knew damn well he was dead. Still, those sounds gave him strange feeling.

That night the men were housed in a small stone building. Fear itself was enough to keep George awake, but he also had a swelling knee that he had injured when landing on the road, along with the pain of the raw nerves of his broken teeth. The following morning, Leo Krebs, who could speak German, talked to one of the guards about George's teeth. The guard spoke to an older soldier, whom George thought may have been the cook. The two Germans sat George down on a bale of hay. With Swanson and Krebs holding George's arms, the old German started toward his mouth with a pair of rusty old pliers. The German's hands were shaking, and at the first grab he got the remaining portion of the first tooth, along with a large chunk of gum. Never in his life had George felt such excruciating pain. The second time the old German's hand was shaking even more. His first attempt to remove the second tooth was a failure, but he got it on the second try. It hurt like hell but at least the pain of the raw nerves was gone.

That same day they were marched down the road, collecting other prisoners along the way. They were taken to a schoolhouse where they joined other American and British paratroopers who were to be interrogated. George was interrogated by a major who spoke perfect English; English that indicated he had been educated in England. However, his English education was all but forgotten when he became angry because he would shout in German when the troopers refused to answer questions about their units. They gave him their name, rank, and serial number which was what the Geneva Accord stated a captured soldier was required to do. Twenty men, including George, were taken outside and stood in front of a stone wall. Two Germans with machine guns were seated about twenty yards in front of them.

George was certain his time had come be killed. After two hours of standing in front of the wall, the men were loaded into trucks to be transported to St-Lo. Approximately two hundred men were in this convoy; Americans, British, Canadians, and some wounded Germans. There was one truck that had a small Red Cross flag on it, but it couldn't be seen from any distance. There were no POW markers on top of the trucks and no other Red Cross markings. As they were moving toward St-Lo, trucks began to pull off to the side of the road. Someone yelled, "Air raid." Men started scrambling out of the trucks and into the ditches. Four British Spitfires came screaming down the road, strafing and shooting up everything within their line of fire. In one of the trucks were two individuals on stretchers, Zol Rosenfeld, a G Company supply sergeant of the 3rd battalion, and a Canadian. Neither was able to move. After the planes made their first pass, both men were screaming for someone to get them out of there. George and several others ran to the truck and pulled them into the ditches. When the planes made their second pass, the truck they had been in was hit. It was a big explosion. Zol told George there were benzine cans in the truck. George estimated thirty Americans were killed on the convoy. The men scrounged up some shovels and buried them the best they could.

What was left of the trucks took them to the outskirts of St-Lo. They were unloaded and marched to the other side of the town where they were locked up in stables. The town was bombed three times that night. All the prisoners could do was lie there shaking and praying as the bombs were going off all around them. They could see the damage as they were taken outside the next morning; the church next to the stable had been totally destroyed.

That same morning George ran into Jim Bradley who was a corporal from his platoon. They were together for the next eleven months, sharing food, bed, and living space. The name for it was ''POW Mucker." In St-Lo they were introduced to a POW diet; one small bowl of very thin soup and a small loaf of bread divided among seven men. George was well on his way to being thin for the first time in his life. They were allowed to walk around in a barbed wire enclosure outside the stable during the day. Allied fighter planes would fly over very low and wave their wings. They knew the POWs were there. George's sister, Mamie, saw a Chicago Tribune photo of some paratroopers sitting against a wall in St-Lo and thought that one of them was George. The one she thought was George was actually Marty Clark from the machine gun platoon. Clarence Kelly was also in the photo, plus two other machine gun men from Hdqs 3/506. Bradley and George were there at the time the photo was taken, but were either to the right or left of the camera. They were a sorry looking bunch of men, having been in captivity for a week with no bathing or shaving, and very little food. They had been through some hellish times.

The POWs were marched sixteen miles out of St-Lo to a monastery. It was a three story building surrounded by expansive grounds and a high wall. There were a lot of books in Braille so George assumed it was a monastery for the blind. The monks were being ushered out as they arrived. The POWs dubbed that monastery "Starvation Hill" because they stayed there for two weeks with very, very little food. Their diet consisted of thin soup for the first three days. Actually, it was little more than warm water. The hunger was so bad that if a man was sitting down and stood up too quickly, he could black out. They learned to get up very slowly. It was all but impossible for the Germans to move any food to them, especially during the day. Anything that moved during the day would be fired on by the allied fighter planes. After a few days at the monastery, one of the guards found some cows and milked them, so each prisoner received about a half cup of milk. It tasted fabulous. George thought some of those cows must have ended up in their soup because for the next couple of days it had some body to it, even a couple of pieces of meat.

Each day more prisoners would join them on "Starvation Hill." Rangers, Canadian paratroopers, and some infantrymen from the beaches. George's little pal, Jack McKintry, showed up. Jack had been was in George's squad, and at only 140 pounds, had been George's relief on the base plate of the mortar. On maneuvers George would carry the base plate for four miles, then Jack would take it. He could only carry it for about a mile before he started wobbling and staggering. George would tell him, "Hey, you little shit, give me that base plate back." They had gotten separated on the way to Germany. George was working in the serving line the day McKintry showed up at "Starvation Hill", and was able to serve him up some thick soup.

A French farmer told the men that the front lines were about two and a half miles from St-Lo. They could hear the artillery as word was passed along that four hundred of them would be trucked further into France. They left in open trucks and there was a steady rain all night and all the next day. They looked like drowned rats by the time they arrived at a newly organized transit camp in Alencon. They were given a bag of rye biscuits, a bunk with a real mattress, two blankets, and a loaf of bread to be shared by eight men. One man would cut the bread as evenly as he could. The man who cut the bread always got the last piece. Along with the bread, they were given a little jam and a cup of barley soup, which was a real feast. Later that evening they received some thin pea soup. Between the food and the real bed, George actually slept for the first time in his fourteen days as a POW.

The next day George's group was taken into one of the main streets in Alencon. They were told if one man escaped, ten men would be shot. They were given picks and shovels and told to dig down to bombs that had gone through the streets, but had not exploded. The Germans would either pull out the bombs or detonate them. The troopers would dig very carefully while the guards stood on the other side of the building, occasionally looking around the corner make sure the POWs were working. While the guards were out of sight, Jim Bradley broke the handles on the picks and shovels so they couldn't do any more work. The next day the Germans showed up with a truck full of handles for the picks and shovels. That took care of Jim's good work. Although George's group never did get down to a bomb, they heard an explosion down the street that made them think another group had found a bomb and had been blown up. The following day, as they were leaning up against a stone wall taking a break, they saw a P-38 coming over. He came flying up the street, very low with machine guns spitting, and bullets flying everywhere. Luckily nobody was hit.

The POWs found themselves on the to move again. This time they traveled all night in covered trucks. They were taken to Chartres, another transit camp, and placed in some old warehouses, with the Americans, British, and Canadians being separated. Again, they had a small loaf of bread for six men and some peppermint tea. The warehouse, containing about three hundred Americans, had cement floors covered with straw. Being involved with straw usually meant lice and fleas. Both became a part of being a prisoner of war. Breakfast the next morning consisted of bread and tea, with thick soup at noon. The Americans could hear their Air Force bombing an air strip near the enclosure. They were told that as soon as the railroad was repaired, they would be on their way to Germany.

Two days later, eighty Airborne men were taken by truck to Paris. The Germans marched them through the streets of Paris. They had loudspeakers on the accompanying trucks announcing that the troopers were murderers and rapists let out of prisons to fight in the war. Men and women would hit them and spit on them as they marched by. George's blood ran cold at the sight of a Frenchman just walking up and smacking one of the soldiers on the head. Jim Bradley was walking in front of George when a young girl started running along side the group, spitting in men's faces. As she started to spit in Jim's face, he spit in hers. George thought, "Boy, are we going to catch hell now." But the guard just pushed her back into the crowd and they moved on. They were taken down to the railroad yards to be put into boxcars going to Germany. While they were in the yard, the German guards would light up a cigarette, take a couple of puffs, and throw it on the ground. It had been at least fourteen days since the prisoners had had a smoke, and some of the men would scramble for the discarded cigarettes. George, a smoker, and Jim Bradley, who was guts personified, both became angry that some of their airborne buddies would do such a thing. When a guard would throw a cigarette toward them, either George or Jim would immediately step on it. They would also step on any grasping fingers that might be trying to grab it. They were cursed by their own men, but they ended the humiliating show.

The men were packed into boxcars with locked doors and no windows. Standing room only. On one end of the car was a bucket with a lid on it for their toilet, and on the other end was a small can of water. Their destination was Limburg, Germany and Stalag 12A. Shortly after the train left Paris, it was strafed by fighter planes. George thought they were trying to destroy the boilers on the engine, which they did. But in the process, some of the boxcars were hit. George's boxcar ended up with 8 or 9 holes in the side which allowed the light to shine through. The train was stopped for several hours while waiting for another engine to be hooked up. The cars were packed with men, with the only ventilation coming from the holes made by the strafing. One had to believe there were no heathens in those boxcars. Everyone was praying up a storm. They moved in the cool of the night. When the train was stopped in the early morning, the doors were opened and they were allowed to empty the latrine buckets and get some fresh water. Then the doors were closed and locked again, and they were off and rolling.

Germany

At 5 o'clock the next morning, the prisoners were unloaded at Limburg and marched through the gates of Stalag 12A. The guards had huge police dogs that constantly circled the columns. The men were individually searched and marched to the showers. It was the first time George had bathed in fifty days. He could have stayed in that shower for a week. Their clothes were sprayed for fleas and lice, then they were moved into circus tents with straw on the ground. The camp had stone latrines with running water, and for the first time since being captured, the men could wash regularly. The following day they received their first Red Cross parcels from the International Red Cross. The prisoners began receiving the parcels on a semi regular basis, usually once a week. Most of the time they would get one box for two men, although occasionally, it was one box for four. George was convinced that the International Red Cross boxes made the difference between life and death for many of the men. With good management, they could have oatmeal for breakfast, a German issue of bread and soup for lunch, and perhaps spam, cheese, and crackers for dinner. However, after fifty days of bread and soup, the Red Cross parcels of powdered milk, chocolate bars, cheese, and spam proved to be too rich. Many of them ate too much and had diarrhea, which was a real problem in POW camps. In fact, some men died from it.

Air raids were frequent in the vicinity of the camps. If the prisoners were outside when the air raids occurred, the rule was to go into the tents, which didn't make much sense to George. They were given cards to fill out which the Red Cross would then use to notify their families that they were prisoners of war. George's family had been notified that he was missing in action. They received German dog tags which were a rectangular piece of metal perforated down the middle. If a man died while a POW, he was buried with half of his dog tags in his mouth for identification. George didn't think much of that. The men were asked what their former occupation had been while a German wrote down their answers A couple of the smart-ass Airborne types answered, "cowboy". Others said "professional soldier." A lot of them said "student." Another said, "rum-runner." George said "golf pro." Of course, one clown said "pimp."

The POWs had dealt with very few mean Germans in France, but Germany was different. They soon found out when the Germans said "move", they moved, and fast. Limburg was another transit camp with French, Indians, Italians, and some Russians. Russians were treated particularly badly by the Germans. They did not receive Red Cross parcels because the USSR refused to recognize the Geneva Accord and the International Red Cross. Many Russians paid for that refusal with their lives.

After a short period of time in Limburg, four hundred of the prisoners were moved to wooden barracks, showered, deloused, and driven to the train station. Their boots and shoes were taken before being loaded on the cars. They were given enough corn beef and bread for three days. The train started at dark, which gave them a feeling of security because they were not strafed as often at night. In the morning the doors were opened and good ol' fresh air came in as they were allowed to empty the latrine cans and get fresh water. The guards told them they would be in their new camp by the next morning. Their boots were returned when they arrived at Stalag 4B in Muhlberg the following morning. They were marched into camp where they were given typhus shots and vaccinated. Upon arrival at the barracks, each man received twelve cigarettes and a quarter of a British Red Cross parcel. They were issued two blankets and slept on slats in bunks that were three high and two across. The compound was primarily English with approximately twenty Americans to each barracks. The English ran the compound like it was just another British colony. They all answered to their "Man of Confidence," who was elected by the men. This Sergeant Major was also the prisoners' direct representative to the Germans.

Of the four camps George had been in, Stalag 4B was by far the best run camp. The Brits had everything organized. The Sergeant Major let the men know in no uncertain terms that he was in charge of the barracks. The Red Cross parcels and the food could be bartered at their exchange store; the money was cigarettes, and every parcel had a cigarette price. The men received Red Cross parcels regularly, along with some fairly decent German rations. After a period of time, they began to regain some of their strength, and were even able to gain some of the weight they had lost on their near starvation diet. For exercise, George and his pal, Jim Bradley, would walk to the Canadian, Dutch, and French compounds. Russian compounds were off limits. The camp had athletic fields where the British and Scots played soccer on holidays. There was also a basketball court, so the men came up with five teams: three American, one Canadian, and one Polish. In the process of lining up a basketball team, George noticed a trooper named Pat Bogie, 82nd Airborne, 508th Parachute Regiment, who was from Wisconsin. Bogie handled himself very well with a basketball, and he was recruited for the American team. Jim Bradley and George adopted him as one of their Muckers, so that made three of them sharing their rations. This worked out very well because Bradley was a non-smoker which allowed them to use part of their cigarette rations to buy more food. Some of the duplicated items from the Red Cross boxes could be traded in for other food enabling the Muckers to eat three meals a day. Their basketball team won the league. There were six Americans captured at Dunkirk who were in the Canadian army. Canadian people would get names of POW's from their newspapers and send them cartons of cigarettes. Because these Canadian/Americans had been in Stalag 4B for so long, they were getting as many as twelve cartons of cigarettes a month, which made them rich men in POW camp economy. They would wager cigarettes on the basketball games, then give two or three packs to the winning team. Since George's team won most of the games, each win was a very big deal because it meant more smokes, and more "money" to buy more food. George felt the cigarette payments made them professional basketball players. During the time George was playing professional basketball, Privates and Pfc's were being shipped out on work details to factories, farms, repairing railroads, etc. The "Man of Confidence", who played on the Canadian basketball team, was in charge of all records. He changed George's records to read Corporal instead of Pfc, so George would not get shipped out. Who said that athletic ability didn't pay off. George Rosie may have been the only American to be promoted while in a POW camp.

As more Airborne came into the camp, George learned that his buddy, Walter Ross, had received a shrapnel wound in the side while in Normandy. He had been in a first aid station that was liberated by the British paratroopers. George was relieved to know Walter was okay and back in England. The weather turned very cold in November and the men had no heat in the barracks. Bogie, Bradley, and Rosie were sleeping in a double bunk with six blankets with each man taking a turn sleeping in the middle-- they called it the warm spot-- until they discovered George was the only one who didn't have to get up in the middle of the night to go to the latrine. That was how George became the night resident of the warm spot.

In early January, 1945, men from the Battle of the Bulge started coming into camp. Some of them were Airborne, but most were from the 106th Division, a very green outfit that the Germans chewed up during the Battle of the Bulge. Soon after that the men started hearing talk about another move. On January 6th, they were taken down to the railroad station and put into German army boxcars. Each car had a small stove with a small supply of coal, along with three days of rations. The old experienced POW's, Bradley, Rosie, and Bogie volunteered to tend the stove so they could be closer to the heat. They were again packed in like sardines, so between the body heat and the little stove, the men were able to keep from freezing. Things were going fairly smooth until some of the new POW's started getting sick-- the men called it a sour stomach-- and started throwing up and had diarrhea. One of the poor guys was crawling to get to the other end of the car to the latrine bucket. He couldn't see where he was going in the darkness, and he was pleading for someone to help him so he wouldn't mess his pants. Men were lying in his path, kicking and swearing at him. George got up and opened the stove door for some light. He started toward the bucket, kicking heads, feet, or whatever was in his way until he made room for the man to get to the bucket. When he went back to the stove, Bogie said, "You could have gotten the hell kicked out of you, you dumb ass." George told him he wasn't too worried about any man lousy enough to refuse to help someone with a sour stomach. They all had been through that kind of pain.

A few days later, they unloaded at Stalag 3B at Furstenburg/Oder. The barracks had not been used for quite some time, so the first thing the men had to do was try to clean up the m

Cart(

Cart(